From desegregation at Little Rock to MLK's Selma-to-Montgomery march to the Cuban refugee crisis, these are major moments when U.S. presidents have deployed troops in America.

The National Guard is a unique component of the U.S. military. The force consists of part-time reserve units that can be activated by either the state or federal governments in times of emergency or war. There are 54 National Guard units based in each of the 50 U.S. states, plus the District of Columbia, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico.

The National Guard traces its origins to the state militias mustered in 17th-century colonial America. At the start of the Civil War in 1861, Connecticut was the first state to call its militia a “National Guard.” The 1903 Militia Act and the National Defense Act of 1916 codified the National Guard as a reserve force that could be activated by both state governors and the president, including for overseas deployments during times of war.

In the vast majority of domestic deployments, the National Guard has been activated by state governments to keep the peace and restore order during natural disasters or civil unrest. But during some extraordinary circumstances, the president has activated the National Guard or federal troops on American soil, including times when the president thought that state leaders weren’t doing enough.

Here are seven of the most historically significant federal deployments.

1.The Civil War

There was no “National Guard” as such during the Civil War, but when war broke out in 1861, President Abraham Lincoln activated the state militias of the Union to fight the secessionist states of the Confederacy.

According to the U.S. Constitution, Congress has the power to “[call] forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.” And through the Militia Acts of 1792, Congress authorized the president to federalize state militias in order to stop insurrections and enforce federal law.

George Washington was the first president to exercise this authority when he federalized militias in Pennsylvania and surrounding states to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion. Lincoln used that same authority during the Civil War. In April 1861, Lincoln federalized the state militias of the Union in order to muster a combined fighting force of 75,000 men at the start of the war.

Read more: Southern States Meet to Form Confederacy

Last Stand of the Confederacy

In march of 1865, Confederate forces made a valiant last stand against General Sherman's advancing troops, but were undone by the most unlikely of errors

2.Desegregation of Southern Schools

The landmark 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, but it took years for southern states to enforce integration. In 1957, the integration of all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, became the first true test of desegregation.

The “Little Rock Nine” was a brave group of nine Black students chosen to integrate Central High. But on the first day of classes, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called in the Arkansas National Guard to block the students from entering the high school, saying it was for their own protection.

A federal judge ordered that the integration of Central High move forward. The next day, Little Rock police officers escorted the Little Rock Nine to school but were met by an angry mob of white protesters.

Frustrated with the state and local response, President Dwight D. Eisenhower deployed 1,200 Army troops to Little Rock and put them in charge of the 10,000 Arkansas National Guardsmen already on duty. Under federal orders, the same National Guardsmen who blocked the integration of Central High three days earlier now escorted the Little Rock Nine safely to class on September 25, 1957.

That wasn’t the last time that presidents were forced to call in the National Guard to integrate a school. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy activated the Mississippi National Guard in order to enforce the integration of the University of Mississippi. A year later, Kennedy deployed the Alabama National Guard to integrate the University of Alabama against the wishes of Governor George Wallace.

Read more: Why Eisenhower Sent Federal Troops to Little Rock After Brown v. Board

Soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division line the streets outside the Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1957.

3.MLK’s March from Selma to Montgomery

In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson clashed with Governor Wallace and federalized Alabama’s National Guard troops to protect the lives of civil rights activists, including Martin Luther King Jr.

On March 7, 1965, hundreds of people gathered in Selma, Alabama to begin a three-day march to Montgomery, the state capital. The march, organized by civil rights leaders like King and John Lewis, was meant to draw attention to unjust laws that made it nearly impossible for Black people to vote in Alabama.

But as the peaceful marchers approached the Edmund Pettus Bridge outside Selma, they were brutally attacked by Alabama State Troopers wielding nightsticks, whips and tear gas. Footage of the police violence was broadcast on live television and became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

Horrified by the brutality authorized by Governor Wallace, President Johnson federalized the Alabama National Guard and sent additional U.S. Army troops to Selma. Three weeks after Bloody Sunday, the march began again. On September 25, 1965, more than 2,000 marchers safely arrived in Montgomery, where King declared from the capitol steps, “No tide of racism can stop us.”

Read more: How Selma’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ Became a Turning Point in the Civil Rights Movement

On Sunday, March 21, 1965, nearly 8,000 people began the five-day march from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights.

4.The Detroit Uprising of 1967

Across the United States, frustrations over systemic racism, police brutality and unemployment boiled over in “the long, hot summer” of 1967. There were over 160 riots in American cities that summer, but none worse than the violence and chaos that erupted in the Black communities of Detroit.

The trouble began when Detroit Police raided an unlicensed, after-hours bar (called a “blind pig”) in the city’s predominantly Black Near West Side. As the police made arrests, somebody threw a brick through a patrol car window. That spark ignited a powder keg of anger in the streets of Detroit that resulted in four days of rioting, looting, fires and armed clashes.

On July 24, 1967, President Johnson federalized 8,000 Michigan National Guard troops in Detroit and authorized an additional 5,000 federal troops to quell the riots. “Pillage, looting, murder, and arson have nothing to do with civil rights,” said Johnson. “They are criminal conduct.”

When the riots were finally suppressed on July 27, 43 people had been killed, 342 wounded and more than 1,400 buildings burned to the ground.

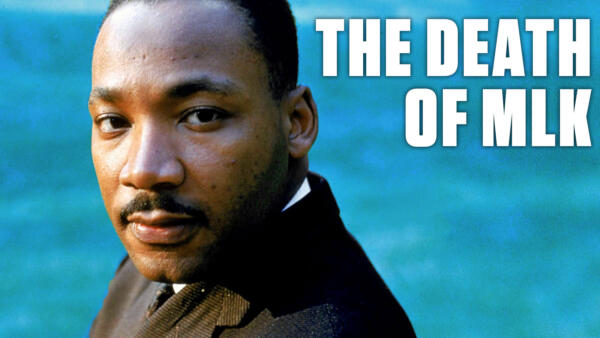

5.Riots Following the Assassination of MLK

The murder of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, was a tipping point for many Black communities in America. The same anger and frustration that had ignited the “long, hot summer” of 1967 exploded again in 1968 with the shocking news of MLK’s death.

President Johnson addressed the nation and urged calm, but violence and rioting erupted in more than 100 American cities, including Baltimore, Maryland; Cincinnati, Ohio; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Wilmington, Delaware and Washington, D.C. To restore peace, Johnson activated 1,750 National Guard troops in the nation’s capital in addition to 12,000 federal troops.

In Delaware, governor Charles Terry refused to pull the National Guard out of Wilmington once the initial rioting was over. Instead, armed guardsmen patrolled the Black neighborhoods of Wilmington for nine months, the longest military occupation of an American city in history.

Read more: Why People Rioted After Martin Luther King Jr.’s Assassination

In March of 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. traveled to Memphis, Tennessee to lead a group of striking sanitation workers in peaceful protest amid threats against his life. The threats were real. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis on April 4, 1968.

6.Cuban Refugee Crisis of 1980

The Air National Guard is the airborne wing of the National Guard, but there isn’t an equivalent for the sea. Instead, if state or federal governments need additional help with an ocean emergency, they call in the U.S. Coast Guard Reserve (USCGR). In 1980, President Jimmy Carter activated the USCGR in response to an unprecedented refugee crisis out of Cuba.

By 1980, many Cubans had grown frustrated with life in Communist Cuba. They suffered economically under American economic sanctions and culturally under the repressive rule of Fidel Castro. For decades, it was impossible to leave Cuba legally, but that changed on May 1, 1980, when a fed-up Castro declared that the door was open. “Those who have no revolutionary genes, those who have no revolutionary blood... we do not want them, we do not need them,” Castro said.

Any Cuban who wanted to leave was directed to the Port of Mariel, the closest port to the United States. For the next six months, they could leave legally. President Carter famously welcomed the Cuban exiles “with open arms,” expecting maybe 5,000 arrivals. Over the next five months, however, more than 125,000 Cuban refugees fled to the U.S. as part of the historic Mariel Boatlift.

The U.S. Coast Guard, accustomed to policing boat traffic from Cuba, switched to a search-and-rescue role, assisting the more than 5,000 boats ferrying Cuban refugees to Florida. In addition to active-duty sailors, more than 1,700 members of the USCGR were activated to assist with the massive rescue and resettlement operation.

Read more: The Mariel Boatlift: How Cold War Politics Drove Thousands of Cubans to Florida in 1980

A boat arrives in Key West, Florida with Cuban refugees, April, 1980.

7.The 1992 LA Riots

In 1991, Americans watched in horror as bystander video footage showed four white Los Angeles police officers beating unarmed Black motorist Rodney King on the side of the road. But the real shock came a year later, when all four LAPD officers were acquitted.

As news spread of the “not guilty” verdict, Black neighborhoods across South and Central Los Angeles exploded in anger. Thousands of people poured into the streets—smashing windows, looting stores and tossing Molotov cocktails. In a gut-wrenching mirror of King’s videotaped beating, a white truck driver named Reginald Denny was pulled out of his vehicle and nearly killed by rioters as news cameras recorded the attack.

The 1992 L.A. riots raged on for three days. President George H.W. Bush invoked the Insurrection Act to federalize nearly 6,000 California National Guard troops. He also sent in FBI SWAT teams, federal riot control police and 4,500 soldiers.

More than 60 people died in the 1992 riots and the property damage exceeded $1 billion.