On July 28, in the closing statements at his trial, 67-year-old Sun Dawu made an impassioned plea for leniency from the Chinese court officials who that day sentenced him to 18 years in prison.

The renowned agricultural entrepreneur, along with family members and colleagues, had spent months in China’s harrowing “residential surveillance” detention system after being arrested last November. Their case went to trial just days after charges were brought to court, leaving the defense hardly any time to review the 348 volumes of case documents.

Speaking at the Gaobeidian Municipal People’s Court in northern China’s Baoding city, Sun—whose incriminating offenses were “provoking trouble” and “gathering a crowd to attack state organs”—choked up multiple times as he described how he and partners built up their business from a modest batch of chickens and pigs to a national brand worth billions.

Sun’s company, the Dawu Agricultural and Animal Husbandry Group, was being accused of multiple economic crimes, which ranged from those involving disputes with state-owned enterprises to unauthorized mining and financial fraud. One charge, that of illegally collecting funds, was something that Sun had previously been arrested and stood trial for in 2003.

Sun admitted that Dawu Group had not always operated in sync with government regulations, but defended his company’s economic successes, worker-friendly “constitutional” model, and civic contributions, while assuming personal responsibility for the legal charges.

“Dawu Group does have its faults, and the fault lies with me alone,” Sun said.

“The charges leveled against Sun Dawu and others, as well as the Dawu Group, are all derived from very trivial ‘disputes’ that can be seen everywhere and every day in China,” Yaxue Cao, editor of human rights website China Change, wrote on the day of the verdict.

The sentencing, she wrote, amounted to a blatant takeover of Dawu Group—which is now under state management—as well as a sign of things to come under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), a Leninist regime that seeks the eventual abolition of private property.

“The CCP has never seen private enterprises as sovereign entities and it can take them over anytime under the guise of implementing the law. That’s precisely what we have seen in the Dawu case.”

‘A Company Built From Eggs’

Dawu Group’s relations with the CCP were not always so antagonistic. Sun was an active participant in the economic reforms of the 1980s, having begun the business in his native Xushui County, a then-undeveloped part of Hebei Province about an hour’s drive from Beijing.

Xushui had been the site where, in the late 1950s, communist China’s founding leader Mao Zedong touted the success of his Great Leap Forward, a disastrous economic campaign that would cause some 40 million Chinese to die of famine.

Born in 1954, Sun’s “first memory was the memory of starvation,” Cao wrote in a feature on Sun. He had joined the People’s Liberation Army at 16, became a Party member at 18, and was discharged after eight years of service.

In 1985, after several more years working at the Xushui Agricultural Bank, Sun decided to take advantage of the economic reforms that were coming to China. Together with his wife Liu Huiru and several other families, they leased a dozen acres of raw land from the government.

Though the others soon gave up—the land had no power, running water, or even roads—Sun and Liu persevered, growing the business from 1,000 chickens and several dozen hogs to 100,000 chickens within several years.

As Sun would later tell an audience at Peking University, “My business was created by bringing land under the plow. It is a company built from eggs.”

Hard work and smart investments in tech and training allowed Dawu Group to grow rapidly. “In 2003, Dawu Group’s poultry breeding group had three hatcheries that could hatch 20 million high-quality chicks per year. Its feed factory produced 60,000 tons annually,” according to China Change.

Sun was well-recognized as a figure in China’s rural economic reforms. He was a frequent speaker at universities, and was even twice invited to offer his thoughts at Zhongnanhai, the CCP’s headquarters in Beijing.

‘Peach Blossom Spring’

What set Dawu Group apart from many other private and state enterprises was no doubt the corporate vision Sun created for the business. Early on, his ethos was “not to aim for profit,” but to prioritize the company’s development and the well-being of employees.

Beginning in 1998, for example, Dawu Group had established non-profit K-12 and technical schools, as well as a 1,000-bed hospital. These facilities and their use were subsidized by the company’s other ventures, making their services available to both Dawu staff and the general public at little to no cost.

Sun also set up what he called a “constitutional system of private enterprise,” based on a triad of “private-ownership, open governance, and co-prosperity.” While the authority of executives and Sun’s relatives was not in question, their powers—and pay—were limited by corporate checks and balances to ensure that employees had fair rights and representation.

According to China Change, Dawu Group never turned a business loss except in 2003, when Sun’s first arrest and legal saga disrupted operations. By 2020, the company had assets totaling more than 10 billion yuan (around $1.5 billion), employed nearly 10,000 staff, and operated 28 subsidiaries.

Despite a stated obedience to the CCP’s socialism, Sun stressed that his model was not meant to create the “involuntary equality” of utopia, nor eliminate all class differences.

For instance, while in court he contrasted his company culture with the authoritarian “model communist” community of Huaxi Village in eastern China—where residents must obey strict requirements in their daily life and purchases, and the leading cadres enjoy unparalleled wealth and privileges. Sun and his colleagues toured Huaxi multiple times, but “knew we couldn’t model on the utopian [ideal], and we had to walk our own path.”

Rather than Marx, Sun took inspiration from the “Peach Blossom Spring,” an idyllic community described in ancient Chinese literature. Removed from the outside world, residents of this paradise managed their own affairs, ignorant of which emperor was on the throne or what his edicts were.

In modern times, such isolation was hardly possible. Throughout his 36 years of operation, Sun faced challenges of varying intensity, from self-serving and spiteful local officials (who on at least one occasion threatened to bulldoze Dawu’s property if the company did not drop a lawsuit) to the CCP system itself.

The local government seemed to “harbor an ingrained disdain and prejudice toward private business,” Cao wrote, describing the petty disagreements and demands that Dawu Group was compelled to handle.

But in May 2003, the authorities arrested Sun and multiple Dawu executives on charges of “illegally absorbing funds,” referring to a sponsorship program that allowed employees and local residents to loan the company grain or cash. The contribution would be sold or invested, and the debtors paid back either immediately or on a schedule.

Despite the flimsiness of the charge, Sun was convicted and sentenced to three years in prison. But a robust defense by human rights lawyers—including currently jailed dissident Xu Zhiyong—as well as prominent media coverage, were instrumental in reducing the punishment, and Sun’s sentence was reduced to time served in detention.

‘This Is Your Last Time Here’

Not coincidentally, Sun’s first arrest and trial seemed to coincide with the high point of his civic activity and lobbying for greater economic freedom.

Though a CCP member and professed socialist, Sun believed in the capacity of the Chinese people to work for themselves. The backwardness and poverty of the countryside, he frequently argued, had little to do with the inability of China’s farmers to turn profits, but stemmed from the preponderance of crushing government regulations and taxes.

“In order to develop the rural market, the first thing should be to let farmers increase their income, and that the way to increase income lies in production plus business,” he said in 1998, during his first visit to the Communist Party headquarters at Zhongnanhai.

Sun spoke for 40 minutes as high-ranking cadres, including then-State Councillor Wu Yi, listened.

But on his way out of the building, a staffer asked if it was Sun’s first time setting foot in the building. When he said yes, the man replied, “then this is also your last time coming here.”

“As I exited Zhongnanhai, I felt no sense of pride, only a feeling of sadness,” Sun would later tell colleagues. “There is still a long way to go to revitalize the rural economy and liberalize the rural economic market.”

The relatively positive, if inconsequential, reception among the officialdom Sun enjoyed was a reflection of the age. Even after the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989, the CCP continued with some reforms throughout the 1990s, with various officials encouraging the growth of the legal community, state enterprise reform, and other steps to transition China into a more conventional and transparent state.

But the leadership of Party boss Jiang Zemin, notorious for his renewed human rights abuses and turning a blind eye to growing corruption, set the country on a different course.

The secretary who warned Sun turned out to be mistaken. He would visit Zhongnanhai again, this time in April 2003. But the atmosphere had noticeably darkened.

“The officials did not introduce themselves, and Sun did not know who they were. He generally reiterated what he had said in his speeches at [two colleges earlier that year]—that there was too much government control and that the peasants were excessively restricted in their economic activity,” Cao wrote.

A month later, Sun was arrested on the fund-collection charge.

Confrontation

Apart from drawing the authorities’ ire for his advocacy of rural reform, Sun was also known as a supporter of China’s rights lawyers, and was not afraid to voice his opinion on other social issues.

“Mr. Sun was a frequent and loud critic of Chinese government policies, from its early handling of Covid-19 to local government cover-ups over a 2019 outbreak of African swine fever that killed thousands of his pigs,” Paul Mozur of the New York Times reported on July 28.

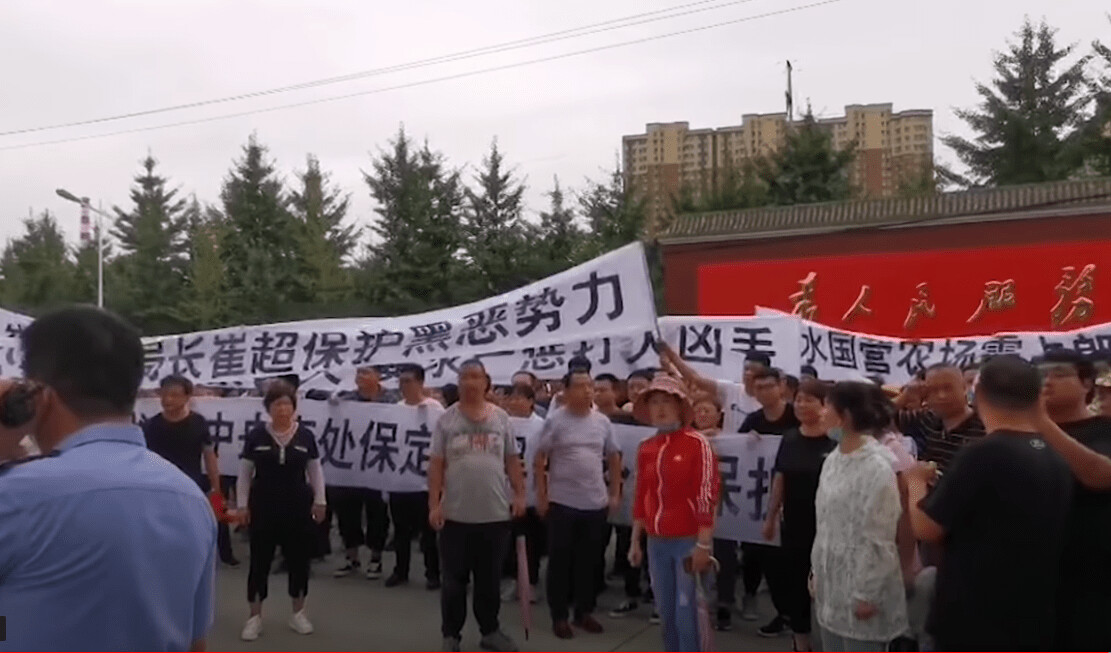

In at least one incident, Dawu staff gathered to protest the local authorities, holding banners and chanting slogans to protect their firm.

The arrests of the Suns and Dawu executives on Nov. 11 came in apparent reaction to a protracted land dispute between Dawu Group and a regional state-run farm.

According to Chinese media reports, the state farm had originally leased about 100 acres from Dawu Group, but steadily encroached on other land owned by the company, occupying more than 300 acres of Dawu’s property. Things came to a head in June and August last year, when workers from the state farm and Dawu Group engaged in physical confrontations and scuffles.

These incidents formed the basis of what the Gaobeidian court claimed was Dawu Group’s “mobilizing a crowd to attack state organs.”

Following their arrest, Sun and other defendants were held in “residential surveillance at a designated location” (RSDL) for more than three months. According to Sun, he never saw the sun during this period of time, and was beaten. Others suffered torture such as being tied up for 30 hours non-stop.

According to a statement from the early stages of the trial, defense attorneys noted “evidence” obtained during the RSDL period was illegal, but the court ignored their arguments.

Sun, his three sons, and 16 other Dawu executives were sentenced in the case. Authorities also started a separate investigation into Sun’s wife Liu Huiru and daughters-in-law for “absorbing illegal deposits.”

Wang Yingguo, an entrepreneur based in southern China’s Shenzhen and an acquaintance of Sun, blamed the “backsliding” direction of the Communist Party for Dawu Group’s setbacks and ultimate fate.

Speaking with the Chinese-language Epoch Times, Wang lamented that the Party saw people like Sun, “who have ideals and create prosperity for the people,” as enemies. “These people are society’s conscience, and they are hard to find. It is they who lead society forward.” But the CCP “is practicing totalitarianism, it is going backward, so any force that stops this backsliding will be increasingly suppressed and destroyed.”

For Cao, the Dawu Group’s accomplishments show “what a private citizen and a private company can do for the country, for a place, and for the people with a little freedom and policy support from the government. But I’m afraid, politically, that’s exactly where the CCP now sees danger,” Cao, the editor of China Change, wrote.

Sun had said in his numerous speeches that China’s countryside had no shortage of talent, labor, capital, or markets; only a lack of freedom.

But as Cao notes, “more freedom is precisely what the Party would not and will not grant.”

No comments:

Post a Comment