For US soldiers tasked with the custody of nuclear weapons in Europe, the stakes are high. Security protocols are lengthy, detailed and need to be known by heart. To simplify this process, some service members have been using publicly visible flashcard learning apps — inadvertently revealing a multitude of sensitive security protocols about US nuclear weapons and the bases at which they are stored.

While the presence of US nuclear weapons in Europe has long been detailed by various leaked documents, photos and statements by retired officials, their specific locations are officially still a secret with governments neither confirming nor denying their presence.

As many campaigners and parliamentarians in some European nations see it, this ambiguity has often hampered open and democratic debate about the rights and wrongs of hosting nuclear weapons.

However, the flashcards studied by soldiers tasked with guarding these devices reveal not just the bases, but even identify the exact shelters with “hot” vaults that likely contain nuclear weapons.

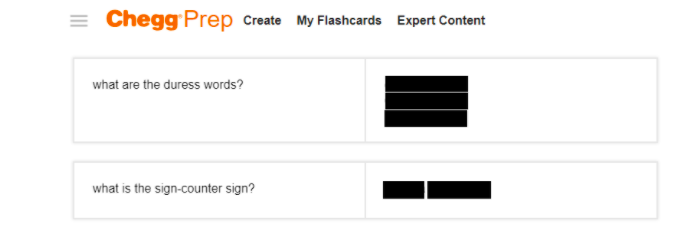

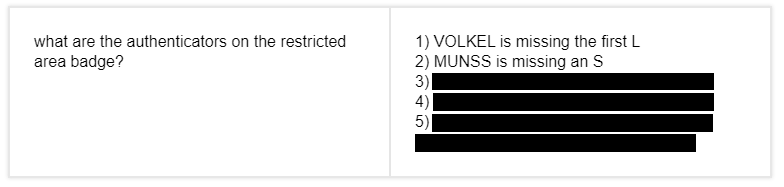

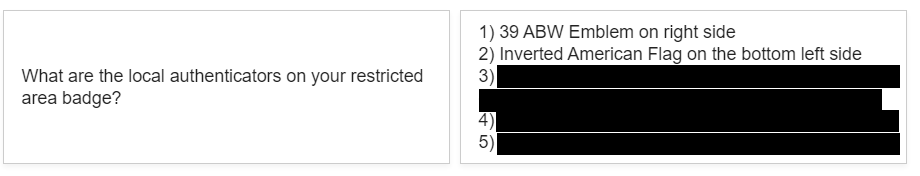

They also detail intricate security details and protocols such as the positions of cameras, the frequency of patrols around the vaults, secret duress words that signal when a guard is being threatened and the unique identifiers that a restricted area badge needs to have.

A Facebook photo posted in 2013 shows US soldiers posing with what appears to be a dummy nuclear weapon at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands.

Like their analogue namesakes, flashcard learning apps are popular digital learning tools that show questions on one side and answers on the other. By simply searching online for terms publicly known to be associated with nuclear weapons, Bellingcat was able to discover cards used by military personnel serving at all six European military bases reported to store nuclear devices.

Experts approached by Bellingcat said that these findings represented serious breaches of security protocols and raised renewed questions about US nuclear weapons deployment in Europe.

Dr Jeffrey Lewis, founding publisher of Arms Control Wonk.com and Director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, said that the findings showed a “flagrant breach” in security practices related to US nuclear weapons stationed in NATO countries.

He added that “secrecy about US nuclear weapons deployments in Europe does not exist to protect the weapons from terrorists, but only to protect politicians and military leaders from having to answer tough questions about whether NATO’s nuclear-sharing arrangements still make sense today. This is yet one more warning that these weapons are not secure.”

Hans Kristenssen, director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, broadly agreed and said that safety is provided by “effective security, not secrecy.”

Some flashcards uncovered during the course of this investigation had been publicly visible online as far back as 2013. Other sets detailed processes that were being learned by users until at least April 2021. It is not known whether secret phrases, protocols or other security practices have been altered since then.

However, all flashcards described within this article appear to have been taken down from the learning platforms on which they appeared after Bellingcat reached out to NATO and the US Military for comment prior to publication. A spokesperson for the Dutch Ministry of Defence stated that it was coordinating with NATO and US European Command (EUCOM) after Bellingcat discovered a picture (shown above) shared on Facebook in 2013 of US service members posing with what appeared to be a dummy nuclear bomb at a base in the Netherlands.

A spokesperson for the US Air Force confirmed that they were aware of service members using flashcard apps to study “a wide variety of subjects”. However, they continued, there was no recommendation for service members to do so and they would not discuss past or current security protocols. They also said they were not aware of any Department of Defense or Department of the Air Force assessment on the use of online study aids but were “investigating the suitability of information shared via study flashcards.”

The Ministries of Defence for Belgium, Germany, Italy and Turkey and Germany — all nations that are reported to host bases where US nuclear weapons are stored — were also contacted about the use of flashcards by US soldiers stationed in their respective territories but none replied before publication.

How Were These Flashcard Sets Discovered?

Military jargon is full of terms and abbreviations, and this also goes for the safekeeping of nuclear weapons. However, online articles, government tender documents and even Wikipedia entries detail some of the key terms.

For example, on bases with nuclear weapons, protective aircraft shelters (PAS) are equipped with Weapons Storage and Security Systems (WS3) made up of electronic controls, sensors, and a vault that is built into the floor. These vaults can each store up to four B61 thermonuclear gravity bombs.

Simply searching for “PAS”, “WS3” and “vault” on Google together with the names of air bases in Europe quickly led to free flashcard platforms such as Chegg, Quizlet, and Cram.

One example is Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands. Although the presence of US nuclear weapons at Volkel has been detailed in leaked documents and statements by retired officials, the Dutch government still considers it a secret.

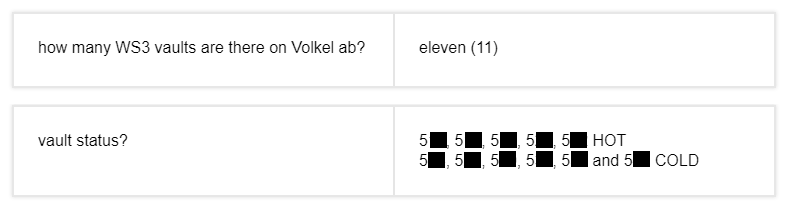

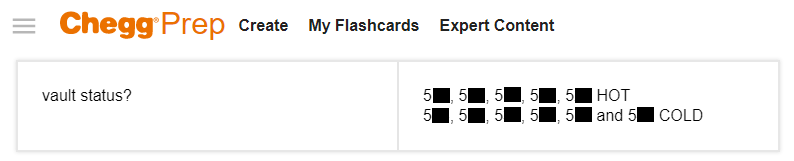

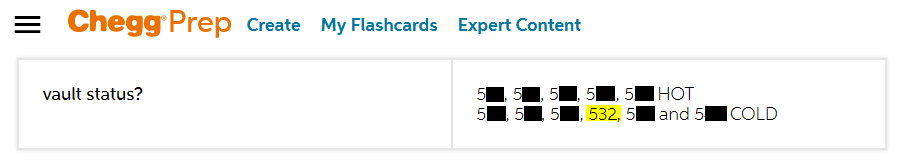

But a set of 70 flashcards titled “Study!” on Chegg appears to go a step further by noting the exact shelters containing the weapons:

Two flashcards created on Chegg in 2019. The numbers refer to the protective aircraft shelter which the vault is in. The last two digits have been censored by Bellingcat.

As can be seen in the image above, five of the 11 WS3 vaults at Volkel are designated “HOT”, and the other six “COLD”.

A different set of over 80 flashcards that apply to Aviano Air Base in Italy, another location where US nuclear weapons are reportedly stored, reveals yet more sensitive details.

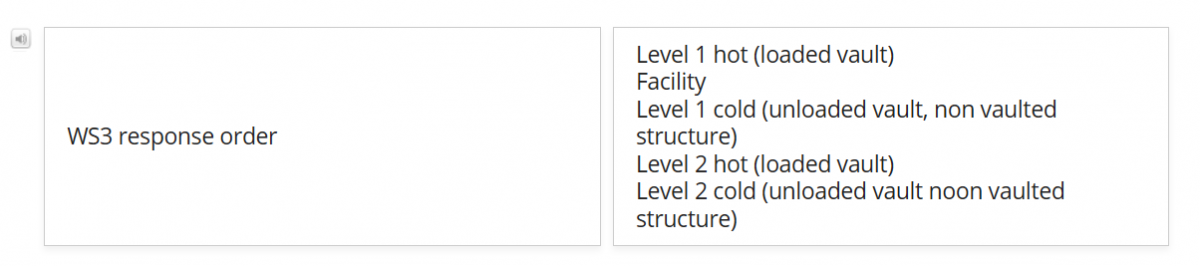

“WS3 response order” appears to refer to the order in which a soldier has to respond to different alarms coming from the WS3 system that is protecting the vaults. For both “Level 1” and “Level 2” alarms, the priority lies with “hot (loaded vaults)” – likely meaning vaults loaded with nuclear weapons. Other cards also use “loaded” and “hot” vaults interchangeably, one did so in context with “nuclear weapon”.

Also at Aviano, another flashcard tells us which vault is cold in “tango loop” (a specific section of Aviano Air Base, also called “tower loop”).

Each flashcard set can contain new definitions and acronyms. Searching for these leads on to yet more new flashcard sets.

At first glance, many appear uninteresting. Virtually all the sets share the same generic textbook knowledge that soldiers learn to pass career development courses. These include definitions of terms, acronyms, forms to turn in, laws, procedures and radio protocols.

But in many cases, servicemen or women have added their own need-to-knows and highly specific security details.

For example, an individual at one base noted down over a 100 things to know related to their specific function. These included the location of modems that connect vaults to the monitoring facility, the procedures for duress signals for each area on base, the sight pictures of cameras aimed at the vault as well as the components and workings of their console. Details around the composition of passwords, usernames and whether they can include spaces were also detailed in the cards.

Some platforms also show when users last studied their flashcards. The user above studied these details most recently in April 2021, although it also appeared to have been removed after Bellingcat contacted NATO, the US Department of Defense and US European Command to ask for a response to the findings of this article.

The information that can be found on flashcards depends on the base being searched for.

Let’s begin with the information most useful for transparency — the locations of nuclear devices (and through the number of vaults, an indication of how many there might be). Apart from new information on “cold” and “hot” vaults at Aviano and Volkel, we were also able to find details of vaults at all the other bases in Europe that reportedly host nuclear weapons: İncirlik (Turkey), Ghedi (Italy), Büchel (Germany), and Kleine Brogel (Belgium).

A flashcard made on Cram in 2014, in a set titled “Incirlik Job Knowledge”. IAB stands for Incirlik Air Base.

Yet perhaps of just as much concern is the open posting of precise information around security and base protocols.

Some flashcards detailed the number of security cameras and their positions at various bases, information on sensors and radar systems, the unique identifiers of restricted area badges (RAB) for Incirlik, Volkel, and Aviano as well as secret duress words and the type of equipment carried by response forces protecting bases.

Then there’s information related to the Protective Aircraft Shelters, the WS3 system and vaults themselves.

Among the details Bellingcat was able to find online for some, but not all, bases were flashcards that detail the buildings where the keys to aircraft shelters are stored, how often “hot” and “cold” PAS are checked as well as specifics on the sensors protecting PAS from intruders and sensors built into the vaults themselves.

Military personnel also detailed information on which items are tamper protected at security facilities, the locations of backup generators and where A and B versions of universal release codes that open all vaults at once.

It is not entirely clear why or how this information became publicly searchable. Quizlet’s website states that all flashcards are set to public visibility by default — users can then change privacy if they choose. Similarly, the help page of Cram’s website instructs users how to make sets private, implying that any flashcards uploaded are also public by default. The Q&A section of Chegg’s website specifies how users can change the privacy settings of their flashcards, but does not explicitly state whether they, too, are publicly viewable by default (in 2018 Chegg acquired its flashcard platform from StudyBlue, whose website is also unclear as to whether flashcard sets were publicly visible by default.).

The Cards

Verifying the information found on the flashcards was relatively straightforward — a straightforwardness which itself presents another obvious security concern.

Some sets made on Cram and Quizlet were traceable as usernames included the full names of the individuals who created them. Others used the same profile picture shown on their LinkedIn accounts.

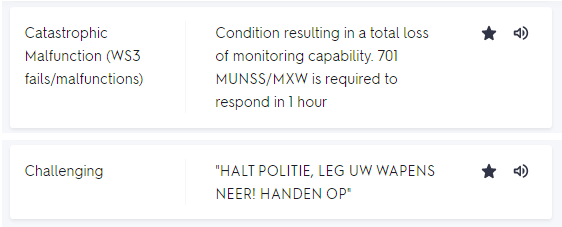

Even in cases where it’s not immediately clear where the user was located, the military base to which their flashcards refer to can be deduced from what they are studying. Some flashcard questions seen by Bellingcat include: What to yell to an intruder in the local language, local laws, the names of squadrons, zones and buildings

Two flashcards from the same set contain the squadron name “701 MUNSS”, and a phrase to make someone surrender weapons in Flemish, revealing that the security details in it apply to Kleine Brogel air base, Belgium.

Other, more subtle, details also allowed for verification. For example, the flashcard that mentioned vault 27 at Tango loop, Aviano air base, matches a public US military document that confirms there is a Protected Aircraft Shelter at Aviano air base labelled “t-27”.

The verification of flashcard content was also required for anonymous sets (without any usernames attached).

One of these appeared to detail procedures at Volkel in the Netherlands.

This information does not appear to be publicly available anywhere else. But it was similar to that found in the sets of verified users at Incirlik, Aviano, Kleine Brogel and others. For example, the anonymous set included a flashcard specifically focussing on the authenticator details of a Restricted Area Badge (RAB), as did those of verified users.

One of the most interesting cards in the anonymous sets was the “vault status” flashcard that appears to note which shelters at Volkel contain nuclear weapons.

In order to fully verify this information, we would first need to establish whether these vaults actually exist. Volkel has 32 protective aircraft shelters (which can be seen on Google Earth), but not every PAS has a WS3-vault. We need to find the ones that do, and check if their numbers match the flashcard.

The Base

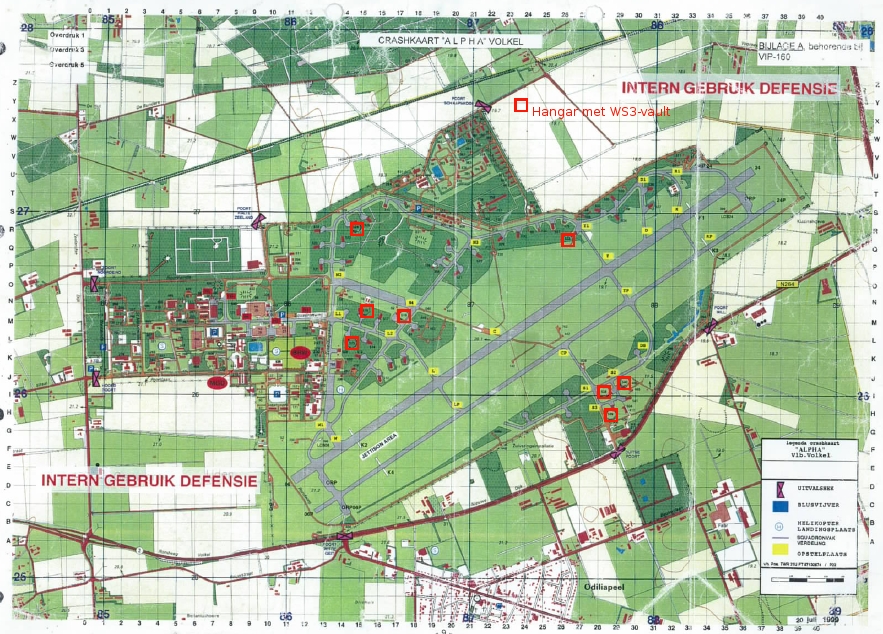

Another quick Google search brings us to a map of Volkel (from 1999), published by Ontwapen!, a disarmament group. It shows eight PAS with vaults — three less than the 11 vaults according to the flashcard (from 2019).

A map showing “Hangars with WS3-Vaults” at Volkel Air Base, labelled “Internal Use Defense” and published by Ontwapen! In 2010.

Several webpages (from 2007 and 2014) can be found which mention shelter numbers that contain the nuclear weapons. Yet the sources behind these posts are unclear and the details only partially match the numbers in our flashcard.

But as Bellingcat’s previous stories about fitness apps and a beer-rating app have demonstrated, soldiers themselves can be an unwitting source of information in these circumstances.

The first step is to find the individuals who have access to these locations. Through Wikipedia, we can see that the nuclear weapons in Volkel are maintained by an American squadron — the 703rd Munitions Support Squadron.

In military jargon, this is abbreviated to ‘703rd MUNSS’ and ‘703 MUNSS’. A quick Facebook search brings up several group pictures — some of which have been shared, tagged and liked by the individuals shown within them. The second step is to explore the open profile of one of these individuals.

There we find a picture shared in 2013.

A picture posted by someone associated with 703rd MUNSS on Facebook. Faces were censored by Bellingcat.

The image was not geotagged, all the individuals wear US uniforms and it was shared by an American on their personal Facebook profile. Anyone scrolling the page could be forgiven for assuming the picture was taken in the US. But some clues confirm that it was not.

Two flags can be seen on the left of the photograph.

The flag on the military vehicle is that of the Netherlands. The text on the other flag ends in UNSS, which matches the name of the aforementioned squadron: 703 MUNSS.

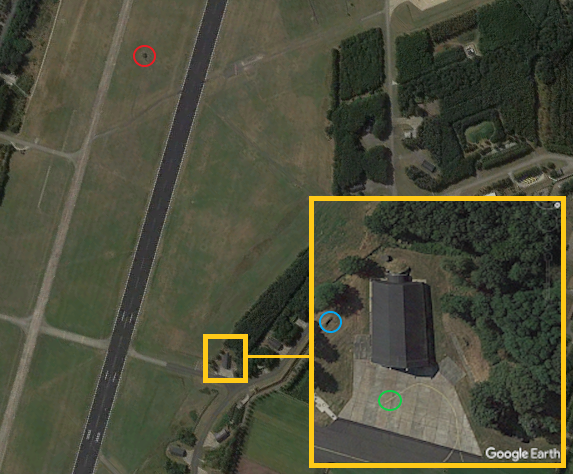

The picture was posted in 2013, but the closest, uncensored satellite image Google Earth Pro can provide of the Volkel Air Base is from 2016. Despite the differences in vegetation in the course of a few years, this satellite imagery can still be a useful guide in finding a match.

Three details in the image from Facebook make one hangar at Volkel Air Base stand out as a possible candidate for the location of the photograph: These are circled in red, blue and green.

Markings, buildings and vegetation in the top image match what can be seen in Google Earth in the bottom image.

Comparing these with satellite imagery shows a correlation. The shape and position of the hangar in relation to the runway, the location of the trees, the position of the yellow line on the ground, the object to the left and the building beyond the runway all match up.

This geolocation also matches a hangar on the leaked map marked as having a “WS3-vault.”

The same leaked map indicates a shelter has number 532. One of the flashcards indeed mentions a vaulted shelter 532.

Therefore, this Facebook picture appears to confirm the flashcard’s information of shelter 532 having a vault. But the flashcard states that this is a “COLD” vault.

According to Lewis, the professor of nonproliferation studies, it would be highly unlikely for active service members to pose with a live bomb. Therefore, Lewis continued, the flashcard information about the vault being “COLD” is likely correct.

But can the details in the picture confirm this?

The Bomb

Let’s take a closer look at the bomb.

A picture posted by someone associated with 703rd MUNSS on Facebook. Faces were censored by Bellingcat.

Nuclear weapons need routine maintenance. The Secure Transportable Maintenance System trailer is specifically designed for that task. It can be seen in the background of the photo above.

According to publicly available documents from the US military, the saddlebag (between the fins) contains cables and accessories for loading the bomb on an aircraft and preparing it for a mission.

The shape also matches publicly available images of a B61 nuclear bomb.

Top: The bomb in the Facebook picture. Bottom: A photo of the B61 as listed on Wikipedia.

The problem is that aircrews use a practice version of the B61, the BDU-38, which has the same shape and size. And to make matters more confusing, the ground crew also have training versions of the B61.

So how can they be distinguished from one another?

Identifying a B61

Practice weapons are usually recognisable by their colours. The B61’s are silver/grey (sometimes referred to as the “silver bullet”), while BDU-38’s appear to be white.

An undated photo, published by the Federation of American Scientists in 2009 but likely taken a number of years before, shows what looks like white BDU-38’s labelled as “inert nuclear bombs” after being dropped on the Netherlands’ only bombing range in Vliehors.

Facebook groups for Volkel aircraft spotters provide another photo of a BDU-38 from 2005 that appears partially white.

Searching for the term white bombs in Dutch (“witte bommen”) on Google leads to another aircraft photographer, who shared photos of F16’s at Volkel carrying the same weapon in 2007. This photographer did not specify the weapon, describing the photos only as Dutch and Belgian F16’s taking off from Volkel to drop “large red-white bombs” on Vliehors. Like the Netherlands, Belgium also hosts B61’s.

By comparing these practice bombs (seen here and here), and the bomb which the American squadron posed (seen below), we can see that even though they have the same shape and size, their colouration is different.

Thus, judging by the silver colour of the bomb which the American munitions support squadron posed with, we can see it’s not a red-white practice bomb used by Dutch aircrews.

Ground-crew training versions of the B61 also appear to have the same silver colour as the device in the Facebook picture but are typically marked with red lettering. Here’s an example of a B61 in a museum. The text in the centre of the bomb reads: “TRAINING ONLY – DO NOT FLY”.

A training version of the B61 at Hill Aerospace Museum, via Flickr

Other examples outside of museums also include red lettering on the nose, the centre of the case, and the fins. It is not possible to tell if the weapon outside vault 532 has these markings.

The only detail that would give certainty is the bomb’s serial number – which we can not see in this photo. According to Hans Kristensen, from the Federation of American Scientists, these weapons “normally have markings with type and serial number. If it’s a real weapon it says B61-x and yyyyyyyyy, a trainer would say something like B61-x Type 3E. But I can’t see markings on the one in the photo.”

An example of a B61 trainer with serial number posted by @Casillic

However, Kristensen added: “I would doubt they would pull up a live war-reserve weapon for a photo op, so my guess would be this is a trainer.”

The protocols and security measures to remove a nuclear weapon from its vault are incredibly strict. If it is an actual nuclear weapon, then the Facebook picture would show an even more significant security lapse.

However, if it’s not a live nuclear weapon displayed in front of shelter 532, it would make sense that the flashcard designated 532 as “COLD”.

Bellingcat asked the US Military and Dutch Ministry of Defence about the photo and whether the bomb was real or a dummy.

While the US Military did not directly respond to this point, the Dutch MoD said it was an inert training version. Yet it added that according to the regulations in force at military bases, “this photo should not have been taken, let alone published.”

‘A Flagrant Breach’

The scale to which soldiers have uploaded and inadvertently shared security details represents a massive operational security failure, or as Lewis puts it, a “flagrant breach” of security practices.

Though this article focussed on personnel working at bases hosting nuclear weapons, they are likely not the only soldiers who are studying using flashcard apps. There appear to be examples of soldiers serving at other US and European bases posting flashcards that detail where cameras are positioned and whether they have thermal imaging.

There also appear to be cards for completely different military uses. For example, Bellingcat was able to find sets with questions about carrying out a drone strike using an MQ-9 Reaper.

Due to the potential implications around public safety, Bellingcat contacted NATO, US European Command (EUCOM), the US Department of Defence (DoD) and the Dutch Ministry of Defence (MoD) four weeks in advance of this publication. The Dutch MoD acknowledged in an emailed statement that it was in touch with NATO and EUCOM regarding this issue. Although it stated the Netherlands does have a nuclear task, it said it could not comment on numbers or locations of nuclear weapons being bound by NATO agreements based on security considerations.

Bellingcat provided links to 50 flashcard sets it found containing security details on Chegg, Quizlet, and Cram — emphasising that the list may not be exhaustive and stating how the sets were discovered. The Dutch MoD informed Bellingcat that the information in these sets did not impact the security of the Netherlands while the US Air Force said: “As a matter of policy, we continuously review and assess our security protocols to ensure the protection of sensitive information and operations.” All of the sets highlighted by Bellingcat appeared to have been taken offline shortly before publication.

For nuclear disarmament activists, however, the information revealed by US soldiers emphasises what they see as the dangers of hosting nuclear weapons in Europe as well as the lack of strategic sense in doing so.

When contacted to comment on these findings Susi Snyder, project leader of the No Nukes program at Dutch peace organisation PAX and coordinator of the Don’t Bank on the Bomb campaign, remarked “The public in European countries hosting B61 bombs overwhelmingly support the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Policies of secrecy that deny democracy can’t last, and risk the security of the population. Secret stationing, like nuclear weapons, are no solution to the threats of today, or tomorrow.”

Kristensen of the Federation of American Scientists added: “There are so many fingerprints that give away where the nuclear weapons are that it serves no military or safety purpose to try to keep it secret. Safety is accomplished by effective security, not secrecy. Granted, there may be specific operational and security details that need to be kept secret, but the presence of nuclear weapons does not. The real purpose of secrecy is to avoid a contentious public debate in countries where nuclear weapons are not popular.”

US Soldiers Expose Nuclear Weapons Secrets Via Flashcard Apps - bellingcat

No comments:

Post a Comment