The latest craze in crypto is changing how we buy and sell things in the digital realm.

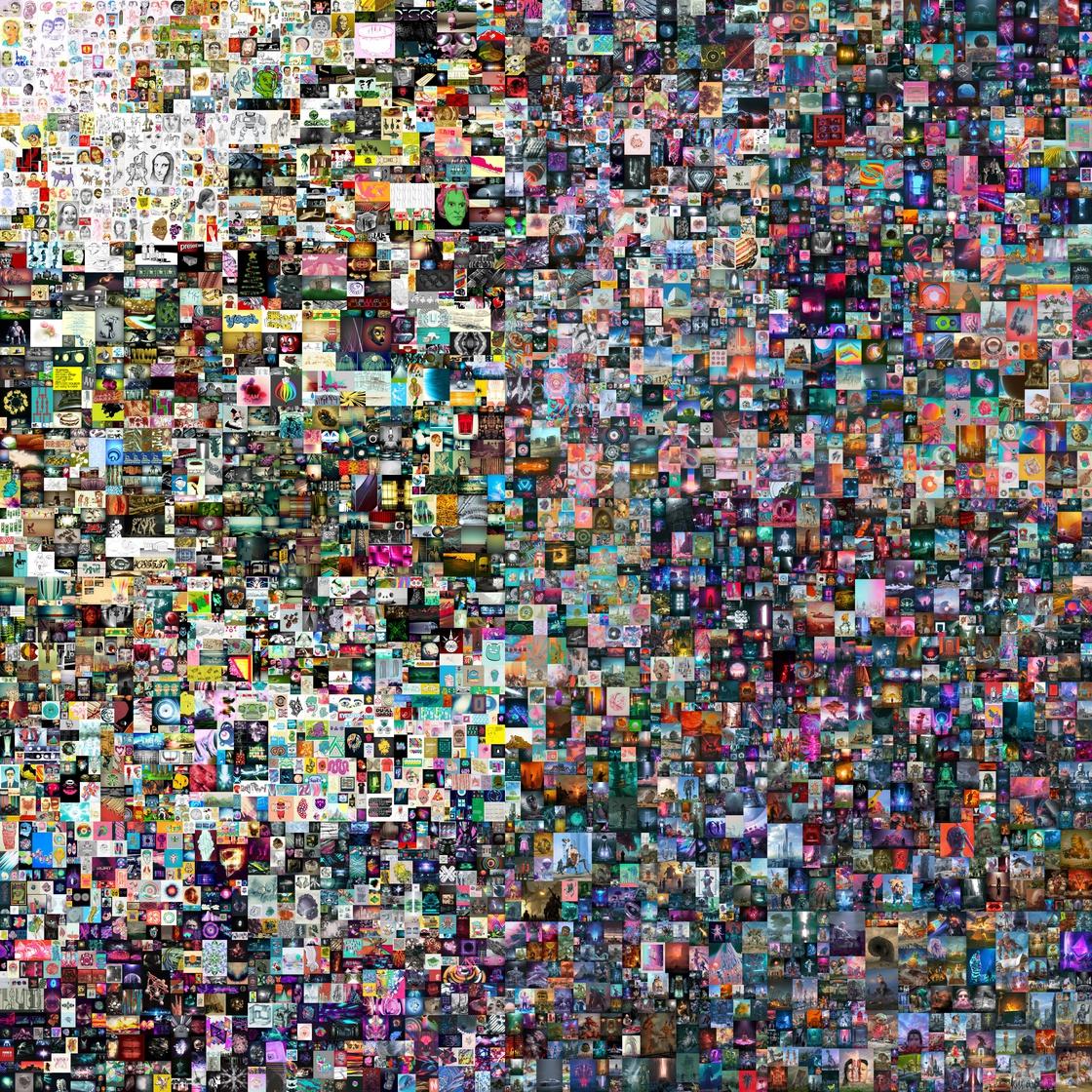

Aherd of googly-eyed cartoon cats. A video of a high-flying Lebron dunk. A digital painting made up of 5,000 smaller images soon to be sold at Christie’s auction house.

All of these have recently been turned into non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, a new method for digitally buying and selling art and other media. These cryptoassets represent the latest blockchain-based boom: Three years ago, the entire NFT market was worth no more than $42 million. By the end of 2020, it had grown 705% to $338 million in value, according to the latest estimate from Nonfungible.com, which monitors the NFT marketplace.

While estimates for the current market size are unavailable, surely it’s grown even more. Just consider the face value of tokens sold in the first two months of the year: Through February, there have been close to 150,000 sales of these tokens for some $310 million—almost quintuple the amount sold in all of 2020.

“This is the future—the coin of the future realm,” says the actor William Shatner, on a Zoom call from his San Fernando Valley home. Last July, the 89-year-old Shatner sold memorabilia from his life and career as virtual trading cards on the Wax blockchain. A 5-card pack was yours for $5. A 25-card pack set you back $25. The collection included candid photos from his Star Trek days...and a 68-year-old dental x-ray. They sold out in nine minutes. One of the rarest cards—a Shatner headshot from the 2000s—recently resold for $6,800. “It’s a phenomenon of rare things being bid up on the internet,” Shatner proclaims.

What is an NFT?

Most simply, an NFT is an entry on a blockchain, the same decentralized digital ledger technology that underlies cryptocurrencies like bitcoin. But unlike most bitcoin–which is fungible, meaning that one coin is essentially indistinguishable from another and equivalent in value–tokens on these blockchains are non-fungible. That means they are unique, so they can represent one-of-a-kind things, like a rare William Shatner headshot or even the title to a piece of real estate.

And because they’re unique and stored on the blockchain, they’re unquestionably authentic. That’s especially important when the asset they represent is digital. Since digital files can be copied infinitely and perfectly, it’s hard to own (or sell) a rare digital photo of Captain Kirk. An NTF token solves the riddle by proving that one digital file is the one-and-only “original.”

Peter Thiel’s Founder’s Fund is an investor in OpenSea, the largest NFT marketplace. The Winklevoss twins own a competitor, Nifty Gateway. JOHN LAMPARSKI/GETTY IMAGES, STEFANIE KEENAN/GETTY IMAGES

When purchasing an NFT, you acquire both the unerasable ownership record of an asset and access to the actual asset. These assets can be anything. At the moment they’re mostly works of digital art or trading cards. Some are virtual goods existing only within the marketplace selling them, and some come packaged in familiar formats like a JPEG or a PDF. A small minority of NFTs are digital records of ownership of an actual, physical object.

When did they start?

Around 2017. Two popular early NFTs were CryptoPunks, digital images of 10,000 human and animal characters in cutesy, 8-bit-style animation, and CryptoKitties, a collection of fancifully drawn felines. They were originally given away for free. The most valuable CryptoKitties now sell for more than $100,000, CryptoPunks for over $1 million. “I wish I could tell you that we knew how it was all going to turn out,” admits Mack Flavelle, one of the cocreators of CryptoKitties. “But we were as surprised as anyone.”

CryptoKitties launched in 2017, sparking a ravenous collecting craze for the NFTs. Today more than 260 of the characters trade hands each week, producing over $2 million in annual sales.

What’s special about the tokens?

For a buyer, they provide a secure certificate of ownership over a digital object, protecting the good’s value. The internet makes it easy to duplicate and forge something, and without an indisputable ownership record such as an NFT, the good is essentially worthless.

For a seller, NFTs make it not only possible to sell something today, but also to keep earning tomorrow. Artists in particular have historically struggled to reap rewards if their work appreciates in value. NFTs can be coded to allow the original creator to collect money each time the token trades hands, usually for between 2.5% to 10% of the sale price. The ability to set up a recurring revenue stream appeals to any famous person looking to extend their fame’s earning potential. For example, YouTube star Logan Paul sold $5 million worth of his own NFT—a cartoon image of himself styled as a Pokémon trainer—last weekend.

“NFTs are the single biggest reorientation of power and control back into the hands of the artist basically since the Renaissance and the printing press,” says Robert Alice, a London-based artist. He sold an NFT through Christie’s four months ago for $131,250, nearly ten times the estimated price. “It appeals to people who have built up their own audiences—maybe on social media—to go and sell work directly to their audience.”

A collage by Beeple for sale at Christie’s; the artist has also collaborated with brands like Nike and Louis Vuitton. CHRISTIE'S IMAGES LTD. 2021

Why are NFTs in the news right now?

A combination of factors. Mainstream celebrities like Paul are latching on to the trend, pushing it into the spotlight. The sales at Christie’s are doing the same, the venerable auction house bestowing a sense of legitimacy to the genre. Next week, Christie’s will finish a 14-day, online sale of a piece by the digital artist Beeple. The starting bid for his work, a virtual collage of pictures from his life taken over 5,000 consecutive days, was $100 and has since surpassed $1 million.

Another major player: NBA Top Shot, a site launched last October for virtual, video-based basketball trading cards. These so-called Moments are sold in five-card packs and then resold in a thriving secondary market; the collections are later displayed in publicly viewable profile pages that function as virtual trophy cases.

Some $200 million worth of sales have already occurred on Top Shot, more than two thirds of the transactions coming within the past week. On Monday, a new record was set when 31-year-old Jesse Schwarz of Los Angeles purchased a Lebron Moment—a clip of a hang-gliding, one-handed dunk during the 2019 Western Conference finals—for $208,000. “People at first were, like, ‘You just spent $200,000. Are you crazy?’” recalls Schwarz. He thinks he could already flip the Moment for $1 million or more. “People’s trust in blockchain has reached a mainstream level right now. This kind of product isn’t scaring people away. . . . Everyone will be on board eventually,” he says with a shrug.

Should you buy one?

Whether purchasing fine art or a 1982 Mouton Rothschild or a CryptoKitty, investing in alternative markets carries greater risk and less reward than money put into more mainstream places, such as equities. A recent study by Citi, for instance, found the Contemporary Art market produced a 7.5% annualized return from 1985 to 2018. Stocks, meanwhile, threw off close to a 10% return. And while NFTs are currently soaring in price, it feels a bit bubbly. The NFT market is largely speculative and probably will have the wild price swings their cryptocousins have experienced over the past few years. Bitcoin, for instance, goes for around $50,000 today. A year ago, it was worth less than a fifth of that.

“There’s a high amount of risk,” says Nadya Ivanova, a close observer of NFTs at L’Atelier, an independent subsidiary of investment bank BNP Paribas. “The important thing to understand about the NFT market is it’s very new. And we’re still going through different cycles that are establishing what is the real value of something.”

No comments:

Post a Comment