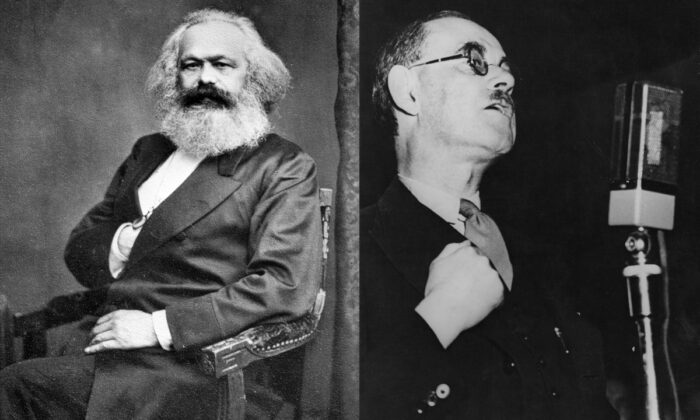

(Left) A portrait of Karl Marx, circa 1875. (International Institute of Social History via Wikimedia Commons) (Right) British political theorist Harold Laski, a leading Fabian socialist, circa 1940. (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Marx Didn’t Distinguish Between Communism and Socialism; Why Should We?

February 3, 2020 Updated: February 5, 2020

Commentary

When President Donald Trump told Fox News host Sean Hannity that he believes the Democrats’ frontrunner, Sen. Bernie Sanders(I-Vt.), is a communist, the president clarified, “You could say socialist,” but then again, “I think of Bernie sort of as a socialist but far beyond a socialist.”

As the pundits trip over poli-sci-class definitions, my question is, what’s the difference?

As far as freedom-lovers go, safeguarding our liberties guaranteed by the Constitution, there is none. To be sure, communists and socialists argue and split hairs. They fight and break heads. But they also work together and destroy liberty because they all travel to the same soul-crushing destination of collectivism.

What anti-communists need to know is that communists and socialists—and “democratic socialists,” Fabians, progress

To that point of ideological convergence, here are a couple of clarifying quotations from recognized experts—one, from the anti-communist camp; the other, from the communist camp.

The first is from Rene A. Wormser, a renowned lawyer specializing in estate planning and taxation who served admirably as the general counsel of the Reece committee, the second of two 1950s congressional committees investigating the Marxist–socialist–communist–progressive subversion of the great American foundations, which undergirded the subversion of our educational institutions over the past century.

Reflecting on both committees’ work, Wormser wrote the following on the topic of “socialist penetration” in his extremely important 1958 book “Foundations: Their Power and Influence”:

“The two recent congressional investigations were largely concerned with ‘subversion.’ The Cox Committee interpreted this term to include only international communism of the Stalinist brand and organized fascism. The Reece Committee, in the course of its work, came to give the term broader or deeper meaning. Neither investigation established sharply, however, the characteristics of Communist activity that would be clearly held to be subversive. In the public mind, the term ‘subversion’ is generally confined to Moscow-directed Communist activity, or that of domestic Communists allied in an international conspiracy. The emphasis on a search for organized Communist penetration of foundations absorbed much of the energy of the investigators and detracted somewhat from the efficacy of their general inquiry into ‘subversion.’“There are varieties of Communist sectarian programs and propaganda of a dissident nature, aside from those directed from Moscow. A follower of Trotsky’s brand of communism may be no less a danger to our society because he opposes the current rulers of Russia. It is likely that there are more Trotsky followers in the United States than followers of the Kremlin. Even among the formerly orthodox supporters of the Party line, there has occurred a mass conversion to a domestic form of the Communist theory and method. Moreover, it is difficult to mark the line beyond which ‘socialism’ becomes ‘communism.’ The line may be between methods of assuming power, communism being distinguished from other forms of socialism by its intent upon establishing a dictatorship of the proletariat. But this line is by no means clear. Socialism has the same ends as communism, though with an allegedly democratic approach. The ‘Communist Manifesto’ of 1848 is the basis of all socialist parties the world over. Marx himself did not distinguish between socialism and communism.”

If Marx didn’t, why should we?

The anti-communist Wormser makes a strong case for intertwining socialism and communism; however, so, too, does his political opposite, the British socialist Harold Laski.

Renowned as a leading British Fabian—yet another term for socialist—Laski was also known as a Marxist (see what I mean about interchangeability?), as well as being a friend and counselor to Franklin D. Roosevelt and just about everyone else on the left in the first half of the 20th century.

In the introduction Laski wrote in 1947 to a new edition of Marx and Engels’ “Communist Manifesto,” Laski addressed the “communist” in the “Manifesto”:

“Why ‘communist’ and not ‘socialist’ Manifesto? Obviously, in the first instance, because it was the official publication of the Communist League. We have little other evidence on which to base speculations. It was possibly the outcome of a recollection of the Paris Commune, an institution to which all socialists did homage. It was possibly a desire to distinguish the idea for which they stood from socialist doctrines which they were criticizing so severely. The one thing that is certain, from the document itself, is that the choice of the term ‘Communist’ was not intended to mark any organizational separation between the Communist League and other socialist or working-class bodies.“On the contrary, Marx and Engels were emphatic in their insistence that the Communists do not form a separate Party and that they ally themselves with all the forces which work towards a socialist society.”

What anti-communists need to bear in mind is the common aggression of socialism and communism against liberty.

Diana West is an award-winning journalist and author whose latest book is “The Red Thread: A Search for Ideological Drivers Inside the Anti-Trump Conspiracy.”

No comments:

Post a Comment