Oregon now allows adverse gender surgery outcomes to go largely untracked, restricts health workers’ right to advise patients about the risks, and strips custody from parents who object to transgender experimentation on their children.

As a group of suburban Portland psychiatric nurses sat for training in late 2016, they had no idea they were witnessing a paradigm shift in public health policy. They simply wanted to know what to do about a sudden upsurge in young psychiatric patients who believed themselves to be in the wrong body. They had turned to a colleague from Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) for help.

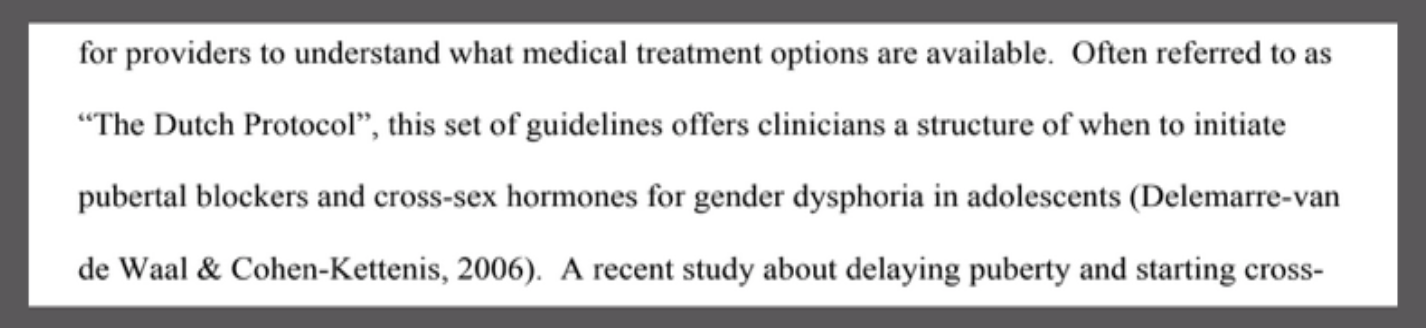

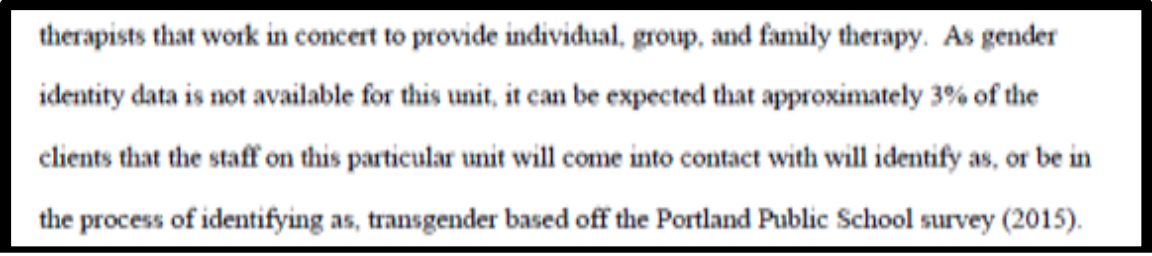

The reply was astonishing: The children’s claims should be taken at face value, and the children should be referred to OHSU, or like institutions, for a “Dutch Protocol” of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. Further, the nurses should expect such referrals to comprise 3 percent of the children in their care.

OHSU has since taken down the URL, but you can find the original PDF from which all quotes are taken here.

What was perhaps most astonishing about this reply went without comment by the nurses or their employer: The citation upon which the 3 percent prediction was based didn’t remotely say what it was derived from. Why didn’t anyone notice or object? To understand that, one must understand the evolving relationship between the gender industry and Oregon regulators.

OHSU is Oregon’s premiere high-volume gender center, with more than a century of experience performing gender-based medical intervention on adults. Lawmakers increasingly trust OHSU to help reshape policies “at the system, community, state and federal level,” and to shape education from kindergarten to doctoral studies, so that on-demand gender-based medical intervention, subsidized by state Medicare, is available to all ages.

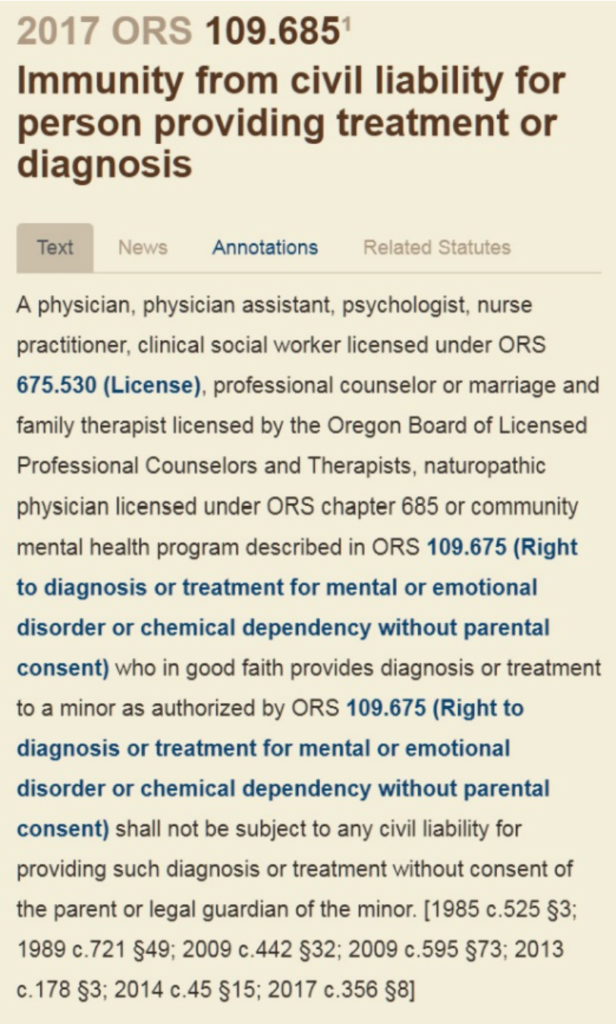

The effect on Oregon’s regulatory atmosphere is palpable. Oregon law now considers anyone over 15 an adult for the purpose of consenting to medical gender intervention without parental knowledge (14when the intervention happens in a mental health setting); and health providers are immune from liabilityfor acting against parents’ objections “in good faith.”

But is “good faith” the proper terminology to describe a public policy set by those who stand to gain financially from it? Economist George Stigler gave it a different name: regulatory capture. Stigler noted that regulatory policies undertaken on the advice of the industry they regulate tend to become indistinguishable from the industry’s marketing objectives.

Stigler would probably not be surprised to learn that, having relied on the good faith of the gender medicine industry, Oregon now:

- Allows adverse gender surgery outcomes to go largely untracked

- Restricts health workers’ right to advise patients about the risks of gender-based medical intervention

- Strips custody from parents who object to gender-based medical intervention on their children.

Nor would Stigler be surprised that no one in the psych ward balked at the idea that 3 percent of children should be referred for gender intervention.

OHSU Distorts the Figures

To put the 3 percent claim in context, it’s helpful to consult numbers the American Psychological Association (APA) published just a few years earlier. In its “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition” (DSM-5), the APA estimated that patients believing themselves to be in the wrong body were exceedingly rare, historically comprising only 0.005-0.014 percent of the male population, and 0.002-0.003 percent of the female population.

By contrast, the OHSU told the Oregon nurses they should refer children for gender intervention at a rate between 200 and 1,500 times the DSM-5’s figures (0.03 ÷ 0.00014 = 214.29 for the lower limit of the range, to 0.03 ÷ 0.00002 = 1500.00 for the higher limit).

Read more:

No comments:

Post a Comment